Approaching Michael Palin in Toronto’s Fairmont Royal York Hotel I ask him how his previous day in Ottawa had been. Thinking I was a fan who recognized him he gives me a generalized answer at which time I realized that I should have introduced myself to him, so starts my 48 hours with one of Britain’s most famous comedians turned traveller and geographer.

A member of Monty Python, past president of London’s Royal Geographical Society and producer and author of eight documentaries and books dealing with travel and geography, Michael was in Toronto to receive the Gold Medal for promoting geographical literacy from the Royal Canadian Geographical Society (RCGS).

Mild mannered, extremely intelligent and obviously funny, Michael was a pleasure to work with even while jet lagged, food deprived, stuck in traffic jams while running late for media interviews, he remained calm and good natured admiring my Formula One driving abilities on Toronto’s congested downtown streets.

Returning to the Royal York Hotel from a media interview that focused on Michael’s RCGS Gold Medal and his new television series and book on Brazil, he and I started talking about the impact the British Empire had on world history.

Nearing the end of the conversation I spontaneously brought up my favorite Monty Python skit, “What have the Romans ever done for us?” from their movie The Life of Brian. Michael and I started to recite the skit. I couldn’t believe that I was reciting Monty Python skits in my car with Michael Palin.

Over the two days I was deeply touched by how many people had approached Michael to express the positive impact his comedy had on their lives. Others were impacted by his travel and geography documentaries and books mentioning the “Palin effect” that inspired them to travel to, and learn more about the geographical areas he had featured.

I asked Michael what sparked his interest in travel and geography and he said that during his youth his parent’s were active in their church and that he “loved missionaries with their tales of losing their arm during a mass baptism. Foreign travel was still an adventure and dramatic, Mount Everest hadn’t been climbed and the Amazon’s source hadn’t been discovered. I was always fascinated by what lay around the next corner, and I also had two great geography teachers who sparked my interest in the subject”

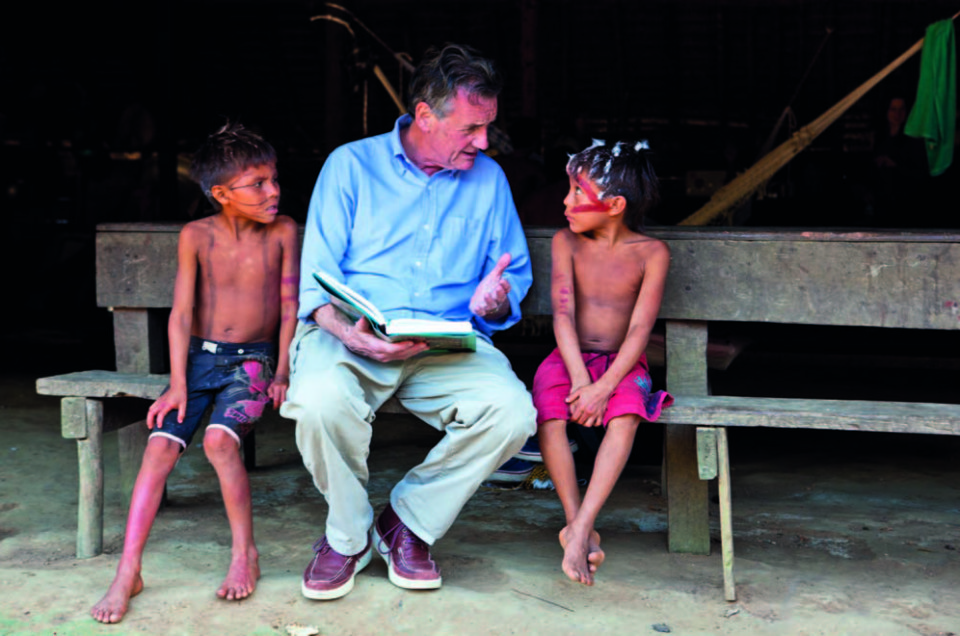

It quickly became evident that Michael supported travel when the traveller interacts deeply and at length with the inhabitants of the country being visited. “To be a good traveller you have to step out of your comfort zone. Take the side roads. Get a feel for the people of different countries and get to know them. You have to understand their culture. Learn a little bit about the country before you leave on a journey and get a local contact through your friends before leaving home. People who don’t engage with the locals are missing out. Letting people off the coach (tour bus) for ten minutes to buy souvenirs doesn’t do anyone any good,” stated Michael.

Michael’s first travel and geographical documentary was the British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) Around the World in 80 Days. This 1989 BBC documentary was based on Jules Verne’s late-19th Century book of the same name. The BBC wanted to see if using the same travel methods as outlined in Verne’s book, a traveller could actually make the trip in 80 days. “The BBC wanted me to act as the English idiot abroad then I realized that I did not need to act,” said Michael with a smile. “In fact when I acted it didn’t work, so I acted natural.”

After the success of Michael’s film A Fish Called Wanda, he thought that the BBC had hired him for Around the World in 80 Days based on his on-screen abilities, but during filming he found out that he was, in fact, the fifth person that they had approached to host the documentary. While shooting in India they attracted a large crowd while Michael was being shaved with a straight razor. Unbenounced to him, the barber was blind. “I thought that it was odd that he was being overly tactile with my face and throat each time he applied the razor to my skin.”

Completing the trip in 79 days and seven hours they returned to London’s Reform Club where they had started their round-the-world journey. Laughing, Michael said, “on our return, when we arrived at the Reform Club, they refused to let us in because they had another function. But of course, you know, the whole purpose of a club is to keep people out.”

Of all his travels, the seven days he spent at sea on a dhow sailing from Dubai to Mumbai with an extended family of sailors from Gujarat, India, had the greatest impact on him. None of the members of this extended family spoke English, nor did Michael speak their language. But they created a strong bond. Twenty years later on behalf of the BBC, Michael visited Gujarat to find these sailors which was documented in Around the World in 20 Years. He was successful in his quest. I watched the documentary a year ago and found it touching; the bonds of true friendship lived on despite cultural differences and time.

The place that Michael remembers most is a Moslem enclave on one of the southernmost islands of the Philippineswith extreme poverty. “People got on with their lives, kept clean, sent their kids to school and were extremely generous to outsiders. I find poor people to be the most generous. They share in order to survive”, reflected Michael.

“I would like to return to Chitral in northwestern Pakistan. The people of Chitral are a great people, very straightforward and they share everything. There is a certain serenity in Chitral as you look out over the Himalayas, an area with only one road leading into it. It is so remote and perceived as being dangerous that the staff of the British embassy never went there and couldn’t provide me with any information on Chitral, so it was all rather amusing when they gathered around me when I returned to listen to my stories.”

Michael felt that there were many places that he took risks but he is an optimist and pushes on. On one occasion outside of Khartoum in Sudan a group of twenty to thirty men surrounded their car and started pushing against it to take the film that Michael’s crew had shot. These Sudanese men thought that they had been filming their poverty.

“Geography is the basis for travel, to understanding our planet and each other. Geography prepares you for an independent view of the world. Geography teaches you that where a country is located has an impact on its people and neighbouring countries,” says Michael thoughtfully. “I’ve learned that the world is a safer place than how the media portrays it. I now know what unites us is far greater than what divides us. That is what geography and immersive travel has taught me.”