It’s nearly impossible to get a cab during rush hour in Amman, Jordan’s hilly, sprawling capital. So, after a solid half hour of haplessly watching occupied yellow cabs creep by on the city’s traffic-choked streets, I was rather happy when two distinguished looking men in a silver Peugeot pulled over to offer me a ride. Despite a firm personal policy of not getting into cars with strangers while travelling in the Middle East, I made a split-second decision, took a deep breath, and climbed into the back. Perhaps sensing my reticence, the driver, pulling away from the curb and back into the languid flow, looked over his shoulder and said with a smile, “Don’t worry! We’re not going to kidnap you!”

Long racked by tension, discord and violence, the Middle East has come into sharp focus as protest and revolution have swept across the region. But, as usual, Jordan—a small nation of six and a half million sandwiched between Iraq, Egypt, Israel, Saudi Arabia and Syria—has proven to be the exception rather than the rule. Proud yet peace-loving, religious yet moderate, dynamic yet stable, Jordan is a bright spot in an area that has seen more than its fair share of dark days.

I ask the driver, Said Haimor—who splits his time between here and another home in California—why this country has, for the most part, shunned both the rising sap of rebellion and the gunfire of its neighbours. (While Jordan was not completely immune from violence, most of the protests that took place here were well-organized, focused on reform rather than revolution, and resulted in far less bloodshed than its neighbours.)

First, he translates my question into Arabic for his friend Isham in the passenger seat, who responds in English: “Because the country is safe and the king is good!” When Haimor and I chuckle a bit, Isham protests. “Seriously!”

Haimor’s own explanation for the situation is a bit more complicated. The country, he says, is made up of a delicate mix of cultural backgrounds, dominated by two groups: Palestinians (many of whom came here as refugees of the 1967 Six Day War), who serve as the country’s economic engine, and Jordanians, who fill the ranks of the military and police. The two need each other—one to generate wealth and pay taxes, the other to protect them and maintain a stable environment for doing business. He adds that the kingdom is more educated than most in the region (literacy runs at 90 percent here, versus 70 percent in Egypt) and that many, like him, travel and live abroad, making them more open and welcoming to westerners. While more nuanced, Haimor’s explanation ended up at the same place as Isham’s. “The Hashemite royal family have kept the balance,” he says.

And everywhere I go in Jordan, I see Hashmite faces—that of the former king, Hussein, the westward-looking monarch who led Jordan for more than four decades until his death in 1999, and that of his son and successor, King Abdullah II, whose visage adorns the walls and even facades of everything from filling stations to hotels and mosques. I trace the family’s lineage at the Royal Automobile Museum, a relatively new institution set amongst the gleaming shopping malls of West Amman. The museum presents the nation’s history through the cars of its kings, from the tricked-out, armoured Rolls Royce Silver Ghosts used by Emir Faisal (a Hashemite) during the Great Arab Revolt, to the silver Mercedes that King Hussein rode atop during his triumphant return from treatment at the Mayo Clinic in 1992, to the rally cars driven by Abdullah II during his pre-monarch days as a daring sportsman.

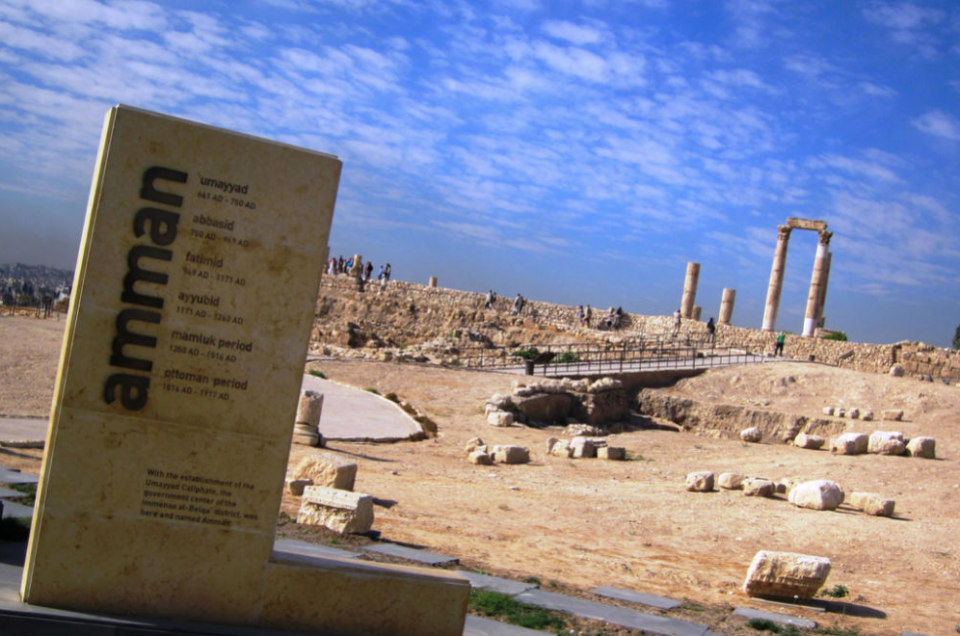

I also take some time to explore the ancient wonders of Amman, one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities. Looming high on a lofty ridge in the centre of the city, Amman’s Citadel Hill holds the ruins of a number of civilizations, including the remains of the second century Temple of Hercules and the National Archeological Museum, which showcases artifacts from the Bronze Age onward.

But perhaps the best reason to visit the Citadel is the view. Built on seven hills, the tightly-packed white and beige homes and businesses of Amman climb the steep slopes all around, a stunning sight to behold. Down below, where I descend afterward, Amman’s lively downtown bustles with life. I walk with the shoppers hustling along King Hussein Street, the core’s primary artery, and then through the city’s colourful open-air market, where cheery vendors selling plump tomatoes and exotic spices sing a cadence, parroting the bargains and deals on offer back and forth to one another. I finish my walk at the city’s splendid Greek and Roman theatre, a three-tiered wedding cake right in the heart of the modern city.

Spotting Hashemite faces all along the way, I head 45 minutes to the west, to the Dead Sea, for the final two nights of my visit to the country. Fed by the Jordan River, the Dead Sea is the lowest point on earth (more than 1,300 feet below sea level) and one of the saltiest—eight times saltier, in fact, than the ocean. Taking advantage of Jordan’s political and economic stability, a number of high-end resorts (complete with pools, palms, cabanas, and man-made beaches) line the north end of the Sea.

Stepping into its cool, blue, slightly greasy waters, I place a small amount on my lips with the back of my hand—and feel as if I’ve been punched in the mouth with a handful of salt. I lay back and experience the sea’s extraordinary ability to buoy items along the surface. It takes no effort whatsoever to float on my back, and I paddle about happily, the dark mountains of the disputed, occupied Palestinian West Bank just on the opposite shore, easily visible to the naked eye.

Later, at dinner, I strike up a conversation with Kamal Al-Jayusi, a jaunty, thirty-something Palestinian-Jordanian guide who is hosting a group of American Christian journalists. (While Israel usually enjoys the undisputed title of Holy Land, Jordan is, in a sense, the “other” Holy Land, home to a number of significant sites from the New and Old Testaments as well as the Koran.) His family displaced and evacuated from the West Bank to Jordan during the Six Day War, Al-Jayusi affirms the key role of the Hashemite kings in maintaining peace and prosperity in Jordan. While he believes that many of the young in the country desire constitutional reforms and increased democratization, he feels that much of the love for Jordan’s monarch is genuine, and very few actually desire regime change here.

And, his face growing suddenly weary, Al-Jayusi suggests another reason why Jordan isn’t eager for revolution. While internally peaceful, the unrest of the country’s neighbours, especially Iraq and Israel, has undeniably had an unfortunate impact on Jordan, a country always caught in the middle. “We’ve had enough,” he says, looking very tired. “I don’t want my two daughters to grow up with all this.”